The craft of winemaking has inspired hundreds of thousands of people to leave city life for the country. For many, having a winery is a life-long dream.

On the surface, winemaking looks simple enough: you gather grapes, throw them in a tank, and then wait. After some time has passed, “voila!” You have wine.

But what is winemaking really like?

In truth, winemaking is an arduous process of observations, sanitization, and practices all for the purpose of shepherding billions of microbes through the bewildering process of fermentation.

Video produced by Guildsomm.com

So, let’s walk through the actual process of winemaking from start to finish.

Winemaking From Start to Finish

There is no single recipe for making wine. That said, there are a lot of well-known processes and techniques that produce the major styles of wine.

It all starts with picking grapes.

Unlike avocados or bananas, grapes don’t ripen once they’re picked. So, they’ve got to be picked just at the right moment.

During the harvest season, this means “all hands on deck.” Harvest jobs are plentiful but they are hard work!

- Some grapes are picked slightly less ripe to produce wines with higher acidity (usually white and sparkling wines).

- Some grapes are picked slightly more ripe to produce wines with higher sweetness concentration (such as late-harvest dessert wines).

- Sometimes the weather does not cooperate and fails to ripen grapes properly! (This is why some vintages taste better than others.)

After the grapes are picked, they’re delivered to the winery.

The winery’s first step is to process the grapes. Wine grapes are never washed. (It would ruin the fruit-quality concentration!) So instead, they are sorted, squeezed, and prodded into submission.

Many types of red wine grapes (like Cabernet Sauvignon) are put on sorting tables to remove “MOG” (materials other than grapes).

Red wine grapes with thinner skins and soft tannins (such as Pinot Noir) are often fermented with their stems to add tannin and phenolics.

Thicker-skinned grapes (like Monastrell) are often destemmed to reduce bitter phenolics and harsh tannins.

White wines are typically not fermented with their skins and seeds attached. Most white wine grapes go directly into a pneumatic wine press which gently squeezes the grapes with an elastic membrane. This is how it works:

The stuff leftover after squeezing the grapes is called pomace. Grape pomace has many potential uses beyond the winery, including cosmetics and food products.

Some white wines soak with the skins and seeds for a short period of time. This adds phenolics (like tannin) but overall, it increases the richness of white wines. (BTW, this is how orange wine is made!)

Juice and grape must is now transferred to fermentation vessels.

There are many different kinds of fermentation tanks. The three most popular types are wood, stainless steel, and concrete. Each has their own unique traits that affect how the wine ferments.

Next comes the most important part: the yeast.

Many winemakers opt to use commercial yeasts to better control the outcome of the fermentation.

Other winemakers develop their own local yeast strains or let nature take its course and allow “wild” yeasts ferment the wine naturally.

Either way, here’s essentially how it works:

Yeast consumes the sugar in the grape must and then poops out ethanol.

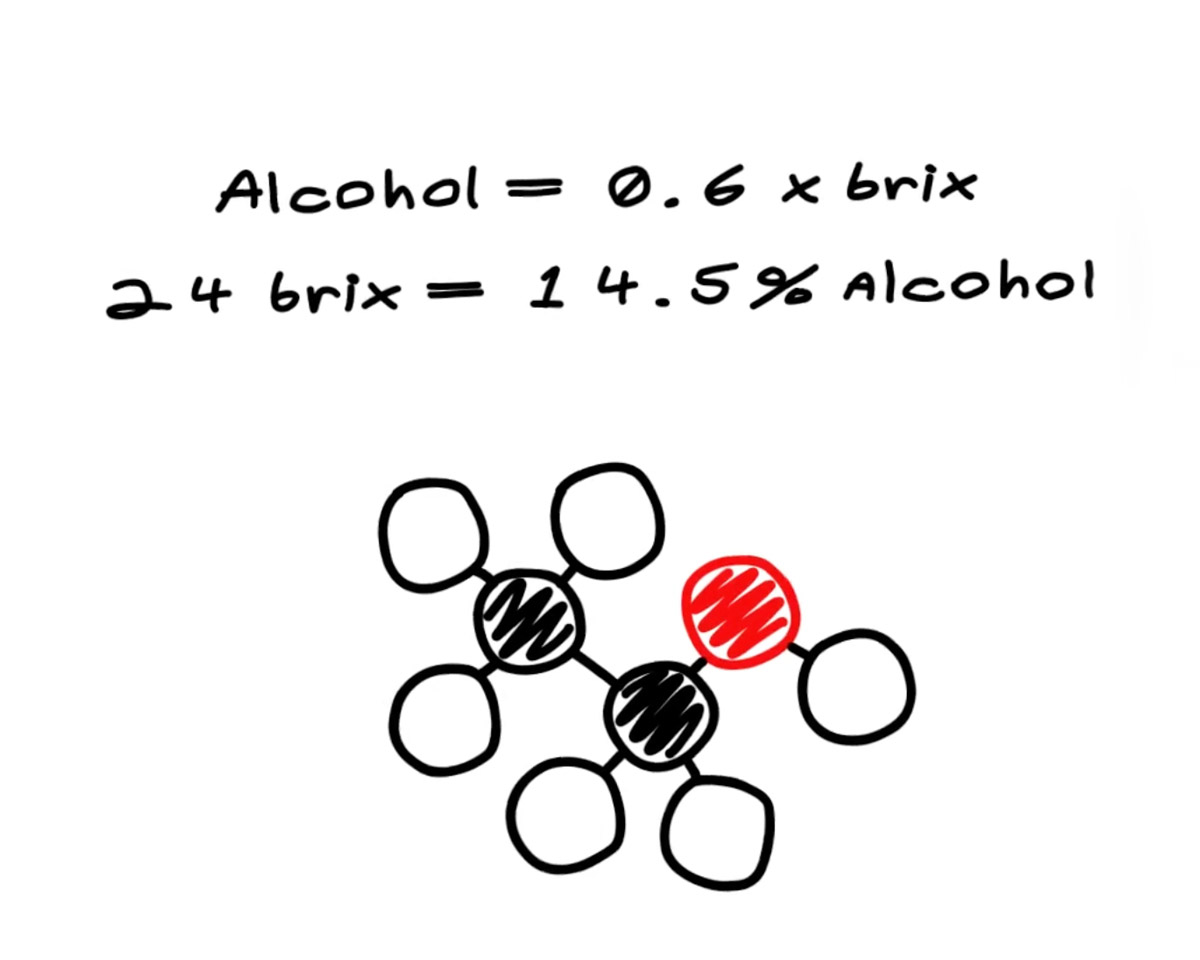

Grape must sweetness is measured in Brix and very basically, 1 Brix results in 0.6% of alcohol by volume.

For example, if you pick grapes at 24º Brix, you’ll get a wine with 14.5% alcohol by volume. (The actual concept is a bit more complicated, but this dirty fast version works!)

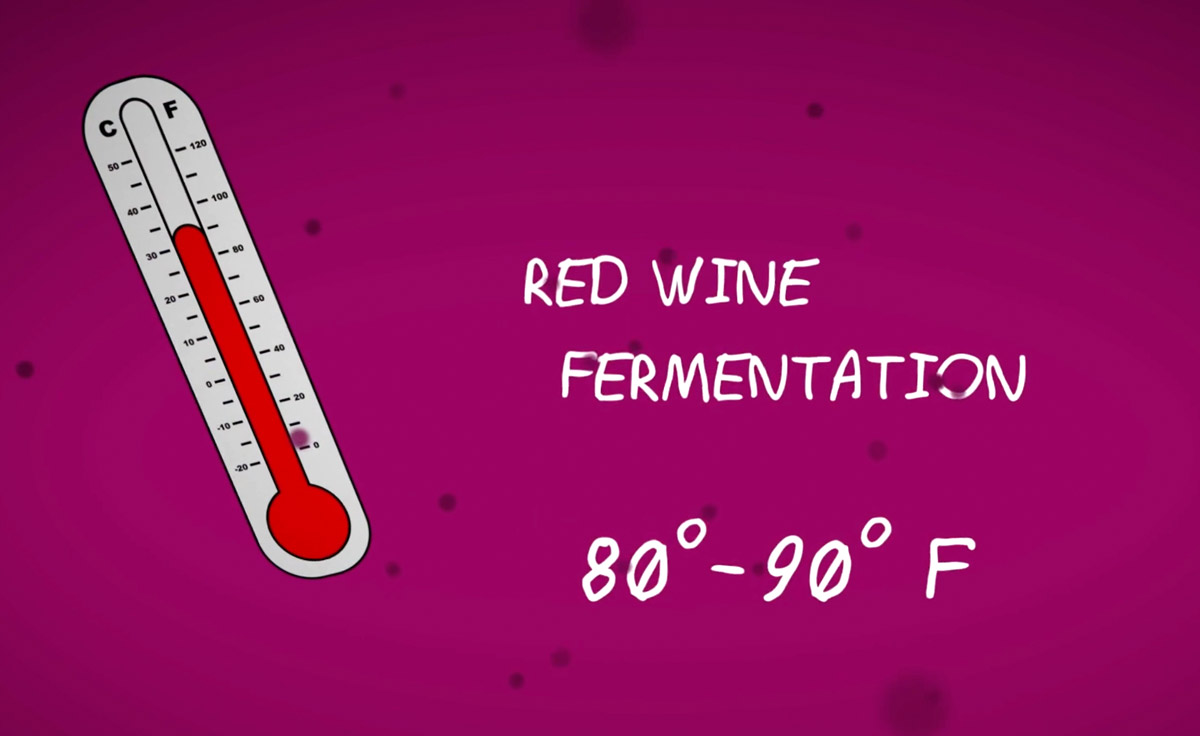

Red wines ferment a bit hotter than whites, usually between 80º – 90º F (27º – 32º C). Some winemakers allow fermentations to rise even higher to tweak the flavor.

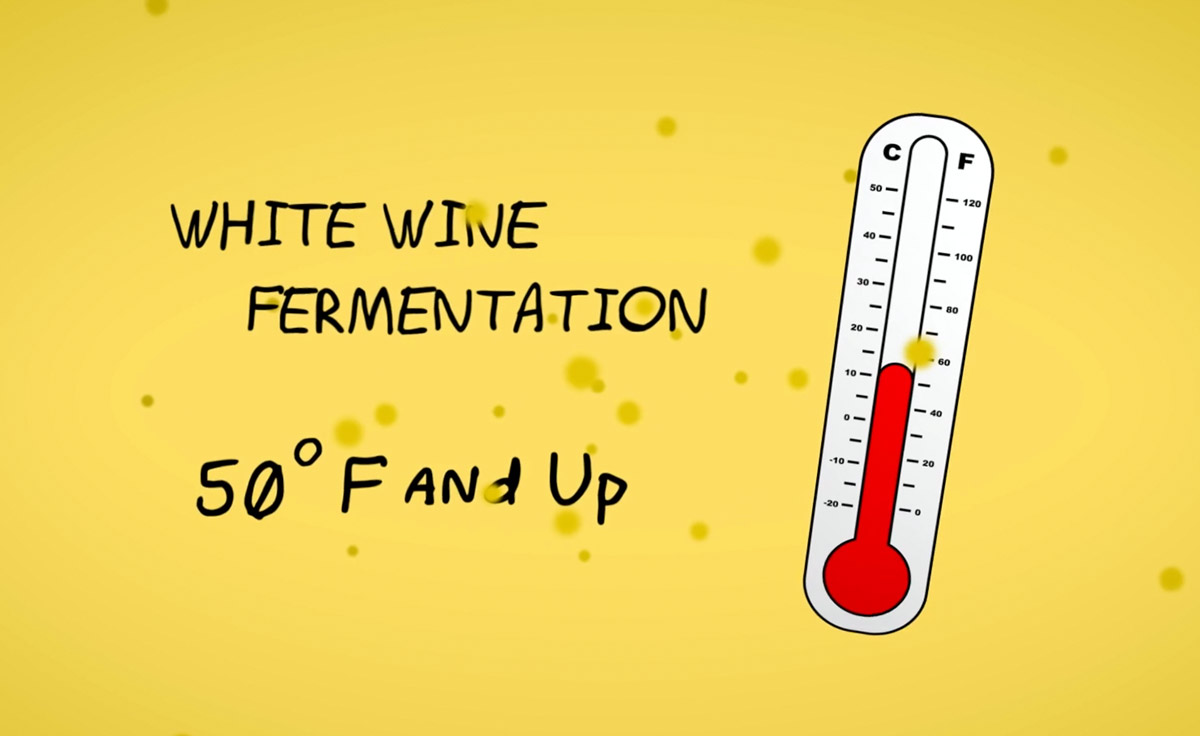

White wines, on the other hand, need to preserve the delicate floral and fruit aromas, so they’re often fermented a lot cooler, around 50º F (10º C) and up.

This is especially true for the aromatic wine varieties (those with high terpene content), such as Gewürztraminer, Riesling, Muscat Blanc, and Torrontés.

While the wine is fermenting, carbon dioxide is released, which causes grape seeds and skins to rise to the surface.

Some winemakers control this by punching down the “cap” three times a day.

Other winemakers prefer to use “pump overs,” where juice from the bottom is gently poured over the top of the skins and seeds.

The choice of “punch down” vs “pump over” really depends on the type of wine grape and desired taste profile. Generally speaking, lighter wines use punch downs and bolder wines use pump overs. But, as with all things wine, exceptions abound!

When the fermentation is done, it’s time to rack the wine out of the fermentation vessel.

The juice that runs free (without being pressed) is generally considered the purest, highest quality wine. It’s called “free run” wine and is kind of like the “extra virgin” wine.

The rest of the wine is “press wine” and is generally slightly more rustic, with harsher-tasting phenolics.

Press wine is typically blended back into the free run wine. (Remember: the less waste, the better!)

Finally, the wine moves into what the French call “élevage.” Élevage is like a fancy way of saying, “waiting around.”

That said, a lot happens in the winery while we wait for wine to cure into something great.

Wines go into barrels, bottles, or storage tanks. Some wines will wait for five years before being released; others, just a few weeks.

During this time, wines are racked, tested, tasted, stirred (lees stirring), and often blended together to create a final wine.

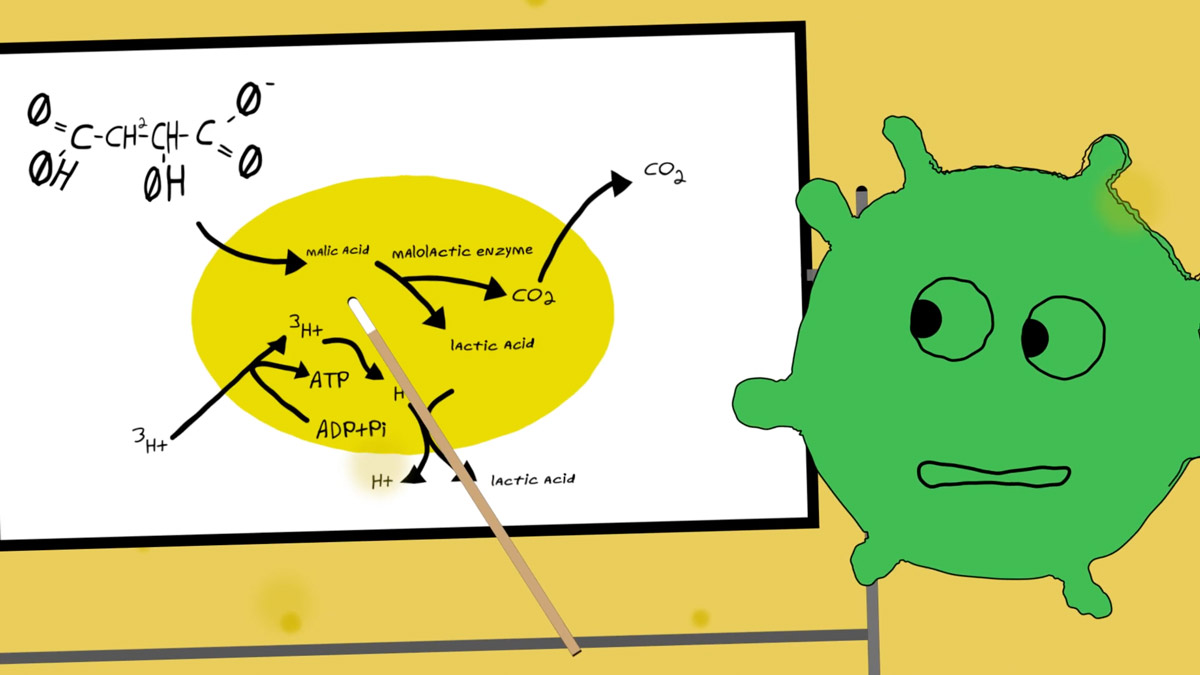

Also, most red wines (and some white wines – like Chardonnay) go through Malolactic Fermentation (MLF), which is where microbes eat sour acids and produce softer, more buttery acids.

So, next time you look at a bottle, think of all the work that went into making it.