I want to show you a snapshot of what the world will be like in 2050 through the lens of wine. Some of you might know about this, and for the rest of you, you might want to sit down.

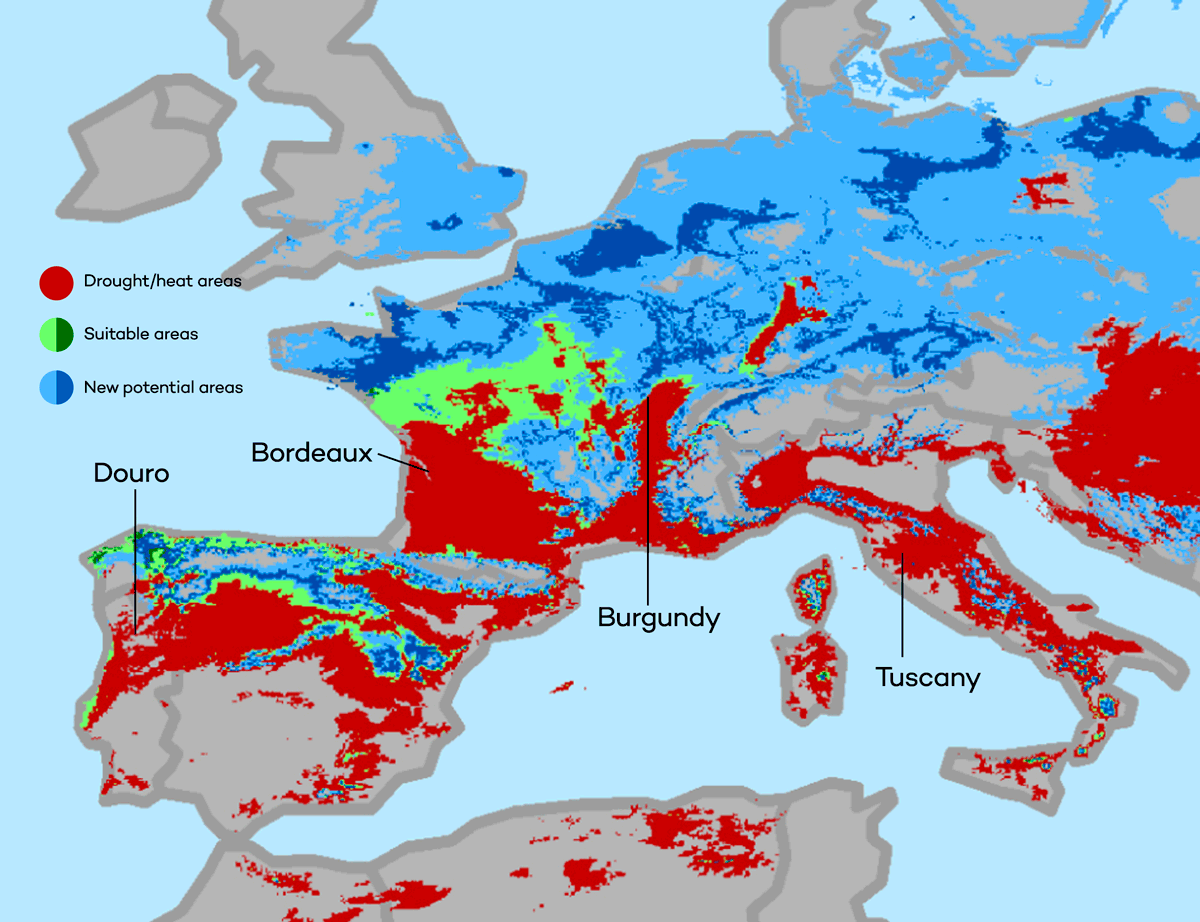

In 2012, a study came out about climate change and its affect on the world’s vineyards. The study used predictive climate information for the year 2050. Then, they cross referenced this data with wine grape physiology info to expose what regions would become less ideal as drought and rising temperatures continue around the globe. It revealed a frightening reality: the world’s best wine regions won’t be able to maintain as they do today.

Want to see where global warming will take its toll? Take a look at some predictive data for 2050.

Wine in 2050

Maps show areas in red will have extreme heat and drought stress in 2015. Maps created by Conservation International

The world’s most important wine regions, like Napa, Bordeaux, Burgundy, Walla Walla, Rioja, Douro, Barossa and Stellenbosch, are on an irreversible course towards excessive summer heat and drought.

Is This For Reals?

Like you, we were a bit skeptical, so we looked further into the story. As it turns out, there was one pretty well-supported argument letter pointing out how adapting farming techniques (and changing consumer preference) will keep these wine regions in operation. They also pointed to how the low data sample rate during sensitive grape growing times would skew data (samples were taken once a month–which was perhaps too infrequent for spring and fall). However, neither group disagrees that these famous wine regions will never be the same.

“…these famous wine regions will never be the same.”

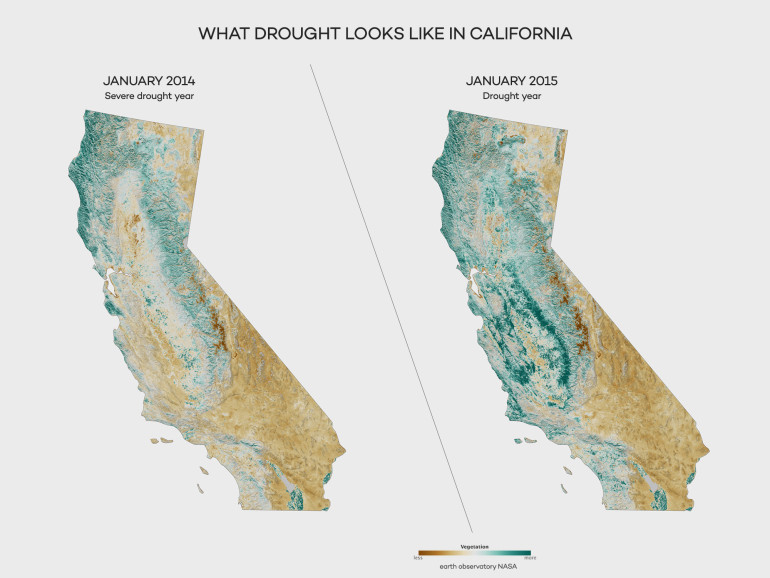

This isn’t the middle of summer, it’s December 2013 before California’s worst drought year. photo by John Weiss

Temperature increases have already shown us big changes, particularly during the most tenuous moments of the year (spring and fall). It’s not that it’s just hotter, it’s that the weather is more unpredictable. For example, late spring frosts in 2014 in Finger Lakes of New York took out the buds in entire vineyards, making it impossible to easily ripen grapes in the next year’s vintage.

A measure of the color of “greenness” of the landscape by measuring how much sunlight is absorbed and reflected by the chlorophyll in plants. You can see how 2014 was a record breaking drought year. Winter storms in early 2015 helped improve the start of 2015, but concerns continue to grow 4 years into California’s most severe drought. Satellite imagery by NASA Earth Observatory

Don’t Give Up Just Yet, There’s Hope

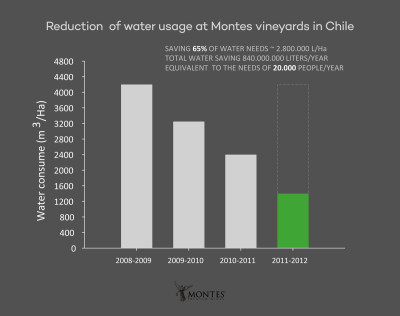

While the US continues to irrigate in most places, other countries are fully embracing change and finding that wine grapes are much more resilient than we ever thought. For example, Aurelio Montes has been testing dry farming on a large scale in Chile.

High skin ratio grapes produce wines with more concentration. by Aurelio Montes

“we started to reduce the use of water in the vineyard [and] we got to amazing results. 1.) The vine can live with less water of what most of the people think, 2.) when you used less water, the size of the cluster and berries decrease, so finally you get more concentration and equilibrium in your wines.” Aurelio Montes

With vines receiving the natural stress of their environment they begin to adapt to it. There is less need to drop crop artificially to concentrate the grapes–vines can’t overproduce when water is scarce.

In the Douro region of Portugal (where fine Port is produced), it’s illegal to irrigate vineyards after their initial planting. In particularly dry years, such as in the 2012 vintage, Portuguese producers will have low wine production but many producers are still capable of making very fine concentrated wines–just a lot less.

In Australia, it seems like the entire country is pitching in. Not only does nearly everyone hang their laundry out to dry (even in central Sydney!) but they also have embraced new wine variety changes to wines made with drought resistant grapes like Tempranillo, Grenache and Mataro (aka Mourvèdre).

In Trentino, the region’s largest wine cooperative company, Cavit, has developed a data-driven regional mapping system (called PICA) that monitors water levels and adjusts irrigation based on the unique needs of each soil and vine type all over the Northern Italian valley. The system not only reduces water usage but also increases overall consistency and quality in the grapes.

Behavior

While we can’t stop the climate from changing, we can slow the damage by adjusting our behaviors. This will buy us all time so that farmers can develop and implement strategies to protect our environment, vineyards and farms.